Tropical Modernism was an architectural style developed in the hot, humid conditions of West Africa in the 1940s. After independence, India and Ghana adopted the style as a symbol of modernity and progressiveness, distinct from colonial culture.

As we look to a new future in an era of climate change, might Tropical Modernism, an architectural style developed in the late 1940s, serve as a useful guide?

Tropical Modernism was Britain’s unique contribution to International Modernism – a colonial architecture, developed by British architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, against the background of anti-colonial struggle in India and West Africa in the late 1940s. This exhibition looks at the colonial origins of Tropical Modernism in British West Africa, and the survival of the style in the post-colonial period when it symbolised the independence and progressiveness of newly independent countries like India and Ghana.

Practical info

“Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence”

2 March 2024 – 22 September 2024

Victoria and Albert Museum

Cromwell Rd, London SW7 2RL

United Kingdom

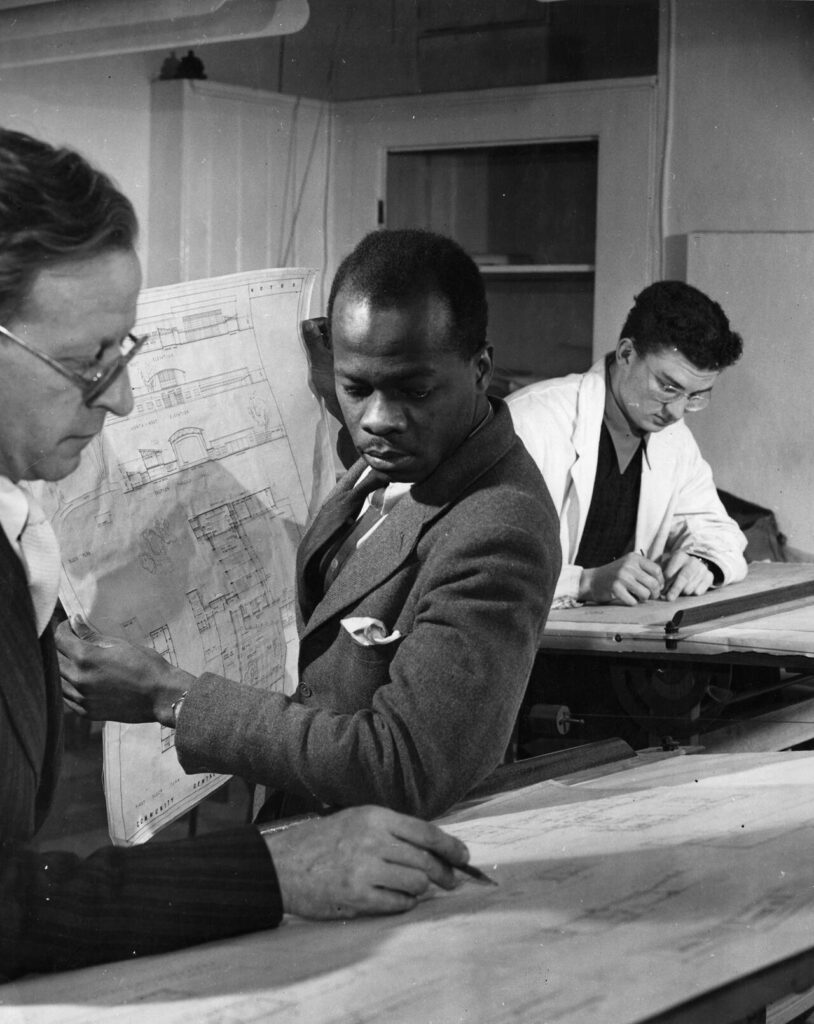

Drew and Fry worked primarily in Ghana and India. Following independence, Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Ghanaian prime minister Kwame Nkrumah commissioned major new projects in this style, using Tropical Modernism as a tool for nation-building and as a symbol of their internationalism and progressiveness. A new generation of national architects more sensitive to local context gave birth to distinctive alternative Modernisms. The exhibition centres and celebrates these practitioners and the alternative Modernisms they created.

Tropical Modernism, despite its colonial associations, became an architectural symbol of a postcolonial future, symbolising the utopian possibility of the transitional moment in which a break with the past was articulated through architecture and new freedoms were won.

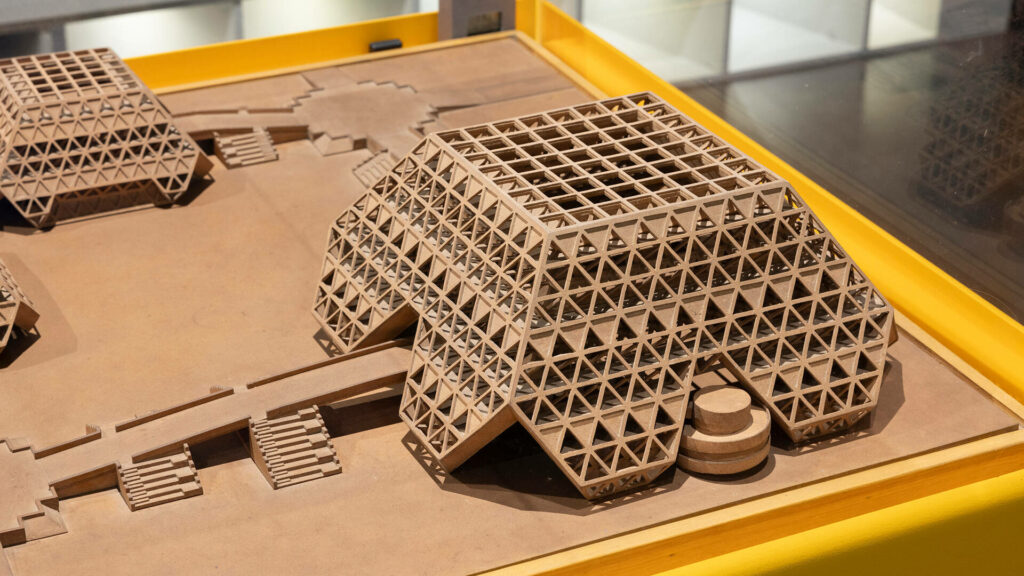

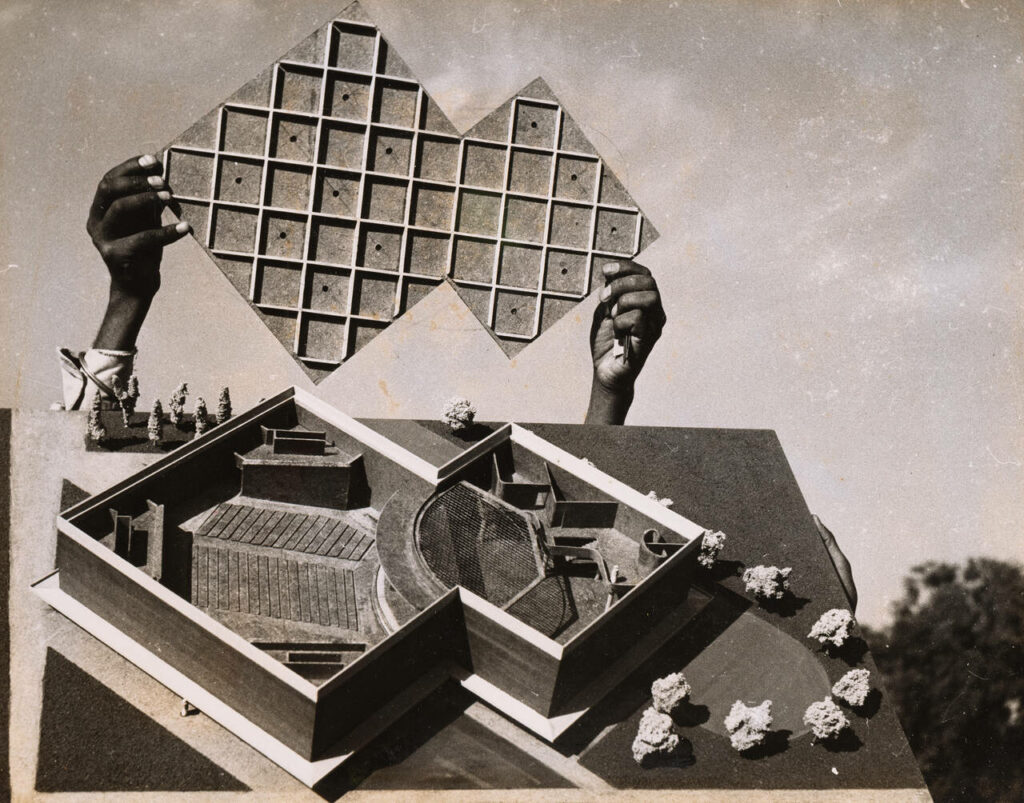

The exhibition will include models, drawings, letters, photographs, and archival ephemera documenting the key figures and moments of the Tropical Modernist movement, and a half-hour film installation displayed on three screens. These artifacts won’t just speak to architecture, but also to modernism’s wider role in narratives about decolonisation and the construction of national identity.

Christopher Turner, the V&A’s Keeper of Art, Architecture, Photography & Design and Curator of the exhibition, said: “The story of Tropical Modernism is one of colonialism and decolonization, politics and power, defiance and independence; it is not just about the past, but also about the present and the future.

The exhibition looks at the colonial origins of Tropical Modernism in British West Africa, and the survival of the style in the post-colonial period when it symbolised the independence and progressiveness of newly independent countries like India and Ghana. We deliberately set out to complicate the history of Tropical Modernism by looking at the architecture against the anti-colonial struggle of the time, and by engaging with and centring South Asian and West African perspectives. As we look to a new future in an era of climate change, might Tropical Modernism, which used the latest building and environmental science then available to passively cool buildings, serve as a useful guide?”

Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence is supported by James Bartos and Celia and Edward Atkin CBE.