With the support of Galerie Eric Mouchet, whose director is also a specialist in Le Corbusier’s work, Louis-Cyprien Rials has set out to give us his vision of an emblematic yet little-known building: the Baghdad gymnasium, designed by the architect at the end of his life and completed after his death, which for a time bore the name of Saddam Hussein before housing a prison.

Artist Louis-Cyprien Rials has made several long trips to Iraq to discover its people. There he observed the rites and vestiges of history, from Sumerian ruins to modern buildings. The Fondation Le Corbusier is delighted to be associated with this project, hosting an exhibition of recent works by Louis-Cyprien Rials from 3 July to 28 September, orchestrated and staged by Guillemette Morel-Journel.

Practical info

“Un stade en Irak”

July 3 – September 28, 2024

The Fondation Le Corbusier

8-10 Sq. du Dr Blanche, 75016 Paris

France

Le Corbusier’s stadium in Baghdad

12 June 1955

A letter from the Iraqi Ministry of Sport arrived in the mailbox of the 35 rue de Sèvres studio. The government wanted to commission Le Corbusier to build a fifty-thousand-seat stadium – a programme that was notoriously scaled back – and a sports centre including a gymnasium with almost 5,000 seats.

12 March 2024

An email from the artist Louis-Cyprien Rials has been sent jointly to the French Embassy in Baghdad, the Fondation Le Corbusier and the Galerie Éric Mouchet in Paris. He is currently working on a project about the stadium: what was conceived in the 1950s, what was built in the 1980s, and what remains of it today, in the second decade of the 21st century.

In the seventy years between these two events, Iraq has been the scene of many political upheavals: the overthrow of King Faisal II, the assassination of Abdel Karim Kassem, coups d’état, the rise of the Ba’ath Party, Saddam Hussein’s accession to power, Kurdish revolts, civil wars, purges, the war against Iran, the Gulf Wars, the embargo, the US occupation, atrocities by paramilitary militias and the Islamic State… On foot, by motorbike, by bus or by train, Louis-Cyprien Rials observes ravaged territories and devastated destinies, as he has already done in Somalia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan, and in many countries not recognised by the international community, as well as in radioactive zones that he considers to be “involuntary natural parks”.

Louis-Cyprien Rials looks at and commemorates what remains of a bygone era of splendour, at a dramatic time: here, in a suburb of Baghdad devoid of any amenities, perhaps less destroyed than the city centre, an enclave, a testimony to a prosperous era when oil was not traded in back rooms : A celebration of sport, a healthy practice for healthy bodies, bodies that wars have not yet broken; a celebration of major events that, while not reaching the global dimension of the Olympic Games, had a vocation that went far beyond the national sphere.

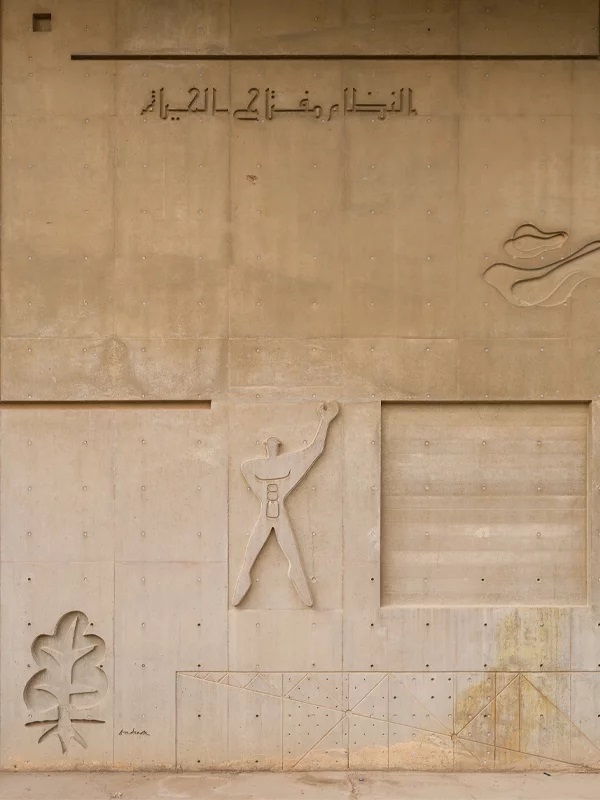

Le Corbusier’s work was never completed: it was delivered in 1980, fifteen years after his death. Today, the stadium almost miraculously retains its forms: here a circular ramp, there the sharp blade of the bleacher roof, there again windows of elusive dimensions. Unexpectedly, when compared with contemporary “modern” buildings, the concrete of the stadium remains very clean, almost too smooth for the raw materials that Le Corbusier was so fond of. In the Tourette convent, as in the Capitol buildings in Chandigarh, spalls and drips gave the façades an almost telluric thickness, while the glazed surfaces of the gymnasium, made by a Japanese firm, seem to foreshadow the impeccable walls that Tadao Ando has been creating around the world since the 1980s.

The Baghdad sports leg is just one part of the Mesopotamian odyssey that Louis-Cyprien Rials has been undertaking since 2011, and whose various stigmata he is constantly bringing back to our comfortable West. Here, it takes the form of three works in the artist’s usual media: sculpture, photography and video, with a foray into botany.

A sheet metal profile

This is the two-dimensional ghost of the silhouettes that are embedded in the concrete walls of most of Le Corbusier’s post-war buildings: the Modulor, a system of measurements based on the Fibonacci arithmetic sequence, which takes the form of a ‘standard’ man measuring 1.83 metres – 2.26 when he raises his arm. This interpretation of a figure typically associated with the architect is echoed in a photograph that confronts the reality of the building today with this ideal image: a woman wrapped in a black abaya, facing the cut-outs in the sculpture, whose lines are dilated by the sun’s rays.

Three videos

In one, Louis-Cyprien Rials has an interview with a man who was imprisoned in the stadium when it served as a prison for the American armed forces from 2003 onwards. Believing he was invited to talk about his painful past, he doesn’t really understand the importance of the building and feels misled as to the reason for the invitation. For him, the walls still echo with the screams of the prisoners, and certainly not with the song of just proportions.

This bogus interview highlights a feeling that is widely shared in the Middle East… The destruction of Palmyra or the Mosul museum may make headlines in the international press, but nobody has ever heard of the Speicher massacre (to name but one). In the West, stones seem to be worth more than blood; in this case, clean concrete more than the tears of Iraqi prisoners.

In the second, the ghost of Le Corbusier, who visits his posthumous work, follows the same path, commenting on his book, finally produced by Georges-Marc Présenté and Axel Mesny. He’s not satisfied either, seeing only the original defects, the additions (stained glass windows, grilles, air-conditioning units, false ceilings) that users have made over the years; and then, above all, his fees, which have never been paid!

In the third, a disabled football team comes to train in the gym, demonstrating the resilience and importance of sport for the Iraqi population.

A herbarium

As early as 1955, Le Corbusier was enquiring about the plants and species to be planted around the stadium, on this desolate wasteland. He asked his local contacts for a list of indigenous species several times, but there was no trace of any feedback. To fill this gap in the archives (or the non-existence of the document), Louis-Cyprien Rials reconstituted a herbarium and presented a selection of plants that, today, could make up the park desired by the architect and whose list could have been submitted to him. He presented this possible list with an envelope addressed to Le Corbusier, bearing his gymnasium as a stamp. However, there is no trace of his name, since only that of Saddam Hussein appears on the stamp. In so doing, he is echoing Le Corbusier’s fascination with the plants that grew ‘naturally’ on the roof gardens of his buildings, and demonstrating another fascination (this time belonging to Louis-Cyprien Rials) with the signs of past glories in the dereliction of the contemporary world by producing L’Herbier rêvé de Le Corbusier (Le Corbusier’s Dream Herbarium).

By revisiting a building that could have been included in the serial list of Le Corbusier’s works inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, Louis-Cyprien Rials also speaks to us of the vanity of public efforts in the name of social progress in a planet on the brink of collapse.