BigMat International Architecture Award’23 is here! Celebrating the opening of this year edition we would like to revisit a great project by Xaveer De Geyter Architects (XDGA) which was awarded with the BigMat International Architecture Award ’13 Grand Prize.

Who will follow Xaveer De Geyter as winner of the Grand Prize? Registration is open now for all the architects in the participating countries. Two Grand Prizes to be awarded on this edition of the BigMat International Architecture Award.

Apart from the BigMat Grand Prize for Architecture (€30,000) this year’s edition features a new Grand Prize for Small-Scale Residential Architecture, also awarded with €30,000, and devoted to any projects comprising the construction, extension or reform of single-family units or small residential compounds up to 1,200m2.

Elishout Kitchen Tower, Anderlecht, Brussels

BigMat International Architecture Award ’13 Grand Prize

Architect: XDGA (Xaveer De Geyter Architects)

Year: 2003-2009

Size: 3300m2

Client: Vlaamse Gemeenschapscommissie

Competition team: Xaveer De Geyter, Henrik Boes Brolling, Lieven De Boeck, Ester Goris, El Hadi Jazairy, David Schmitz

Definitive design team: Xaveer De Geyter, Anouk Kuitenbrouwer, Piet Crevits, with Wesley Aelbrecht, Raphaël Cornelis, Fuminori Hoshino, Ingrid Huyghe, Jarrik Ouburg, Olivier Renard, Marie-Pierre Vandeputte, David Van Severen

Implementation team: Xaveer De Geyter, Raphaël Cornelis, Ingrid Huyghe, with Piet Crevits

Consultants: Barbara Van Der Wee (restoration), Ney & Partners (structure), Studiebureau Boydens (mechanical)

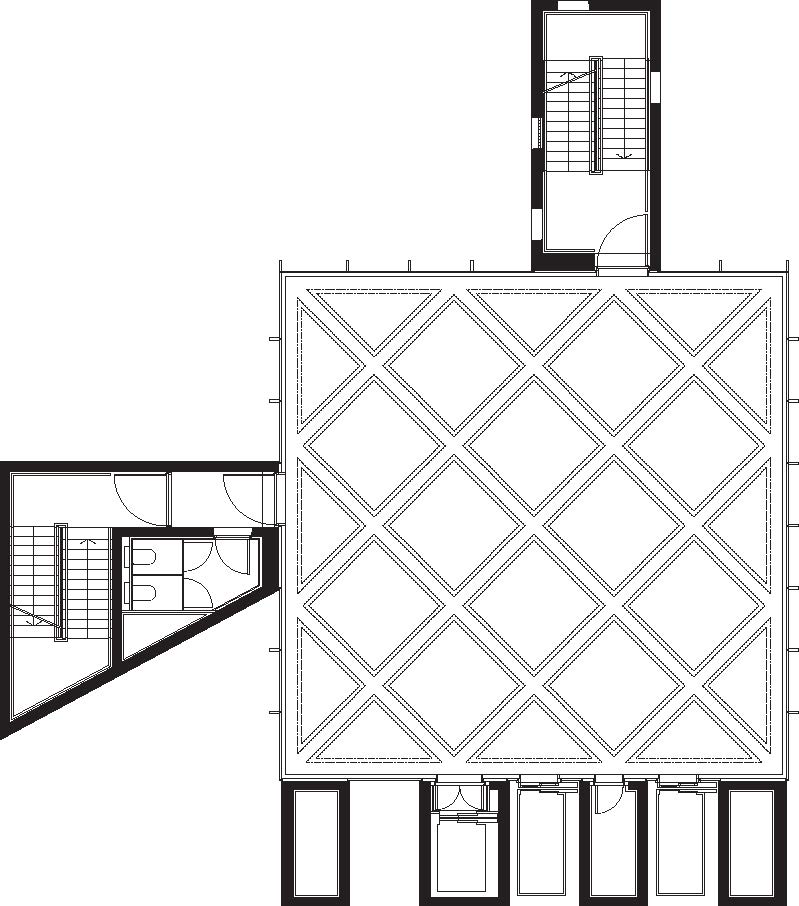

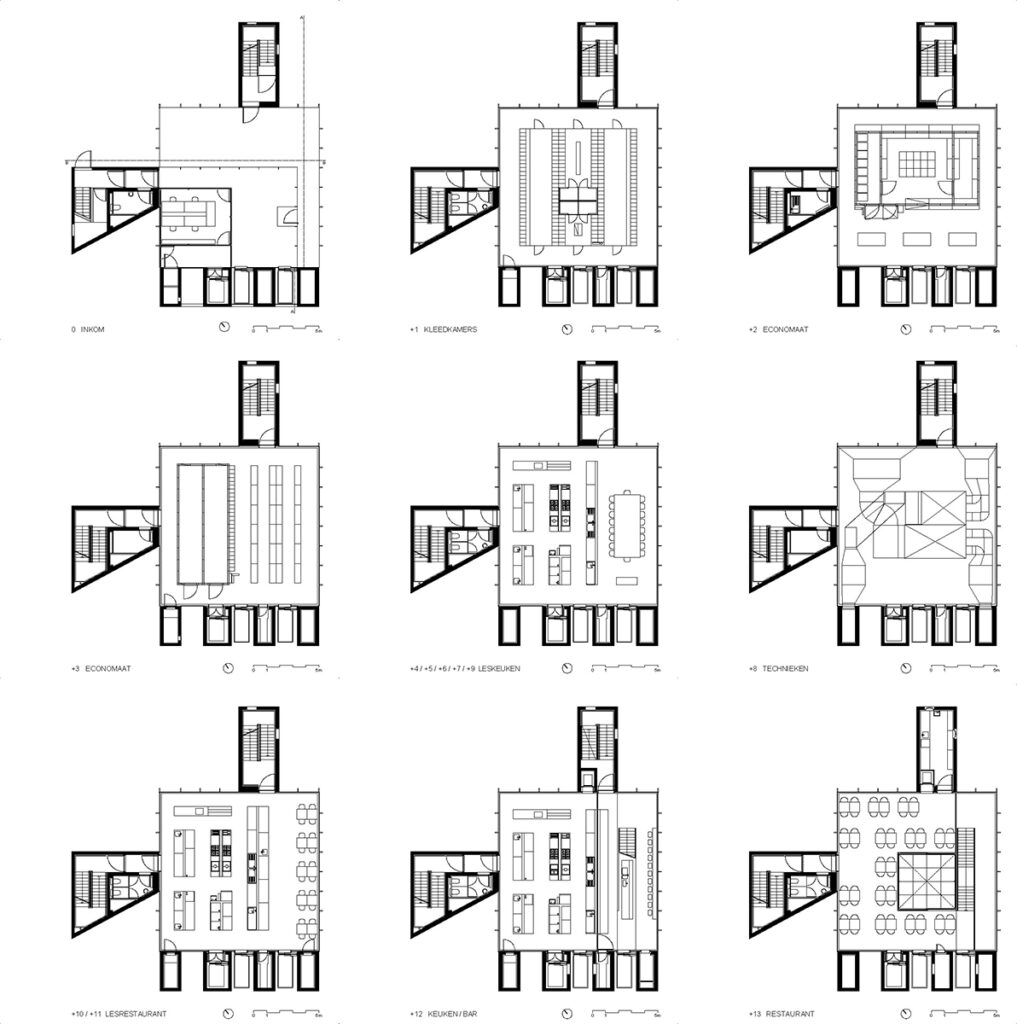

Photos: Frans Parthesius

Xaveer de Geyter’s project for a higher education institute for workers in the hospitality industries takes the programme – eight training kitchens for future cooks – as a pretext for a building that presents itself as a marker, or a signpost, in the infrastructural landscape. The ‘kitchen tower’ is attached to an existing campus of three, four and five storey buildings arranged in open, landscaped courtyards. Rather than seeking a continuation of this pattern, which provides a fairly civilised environment in which to wander, the new building is approached axially. It is a destination that sets itself apart. The concept of the tower is quite simple: the kitchens are stacked one on top of the other, with two emergency staircases on the west and north sides, and a series of four shafts facing the motorway, one of which contains the goods lift. The pattern of a core that serves any number of floors is thus reversed. Volumetrically, the building emerges as a diagrammatic extrusion of the footprint. The exceptions provide the arrangements for the entrance at the bottom and the double-height panoramic restaurant at the top.

The building is part of a masterplan designed to conduct the splitting up of the previously bilingual hotelschool CERIA-COOVI. But perhaps more important is the adaptation of the campus to the new urban context. The hotelschool, a unity of modernist independent buildings set in park-like surroundings, dates from the fifties and was built on the outskirts of Brussels which were still green and rural at that time. Meanwhile, the city has expanded to these outskirts and the campus is now constricted by the ring road around Brussels.

The masterplan consists of a new sports hall with cafeteria which also functions as a new entrance pavilion and establishes a connection with the surrounding houses. Several buildings are being restored and undergo a change of program while the construction of a new boarding school is planned.

Right along the ring road, an area that is usually only interesting for companies to erect offices, a tower is put forward on a central axis from the campus towards the south-west, thus suspending the campus between an existing water tower and the new kitchen tower.

The building itself is a reversal of the classic high-rise concept. It is a stacking of kitchen classrooms, including storage, changing rooms, a bar and a restaurant. The configuration of a central core containing all of the vertical logistics and ensuring the stability of the building as well as the program around it, would not fit here. The disproportion of the relation between the limited program of the stacked kitchen classrooms and the necessary vertical logistics lead us to suggest a configuration with the classrooms in the centre and all of the necessary cores draped around it.

On the side facing the campus, a black perforated volume features an exterior fire escape. An interior staircase and toilets in a gray concrete trapezium shape are situated on the north-west side. Towards the ring road, a ‘filter’ consisting of four white shafts containing the building’s technical equipment, including the powerful air conditioning system of the eight kitchens, as well as a service elevator, functions as a sun screen. Two panoramic elevators are situated in the spaces in between these elements and carry the building’s visitors. The whole of these vertical elements offers a kinetic impression when approaching the building on the ring road by car.

The series of cores carry the central slabs of 12 by 12 meters, thus completely clearing the central space of any structural element. For hygienic reasons even the details of the glass facade are positioned outside.

The building functions as an autonomous entity within the campus. The stacking starts with reception and delivery areas on the ground floor. Going up, we first find three different levels of storage and changing rooms, then there are eight levels of kitchen classrooms where, through their total transparency, the act of cooking becomes theatrical. A technical level has been created at mid-level of the tower. The whole is crowned by a two-leveled bar-restaurant featuring an exterior patio in the middle of the square space and offering a panoramic view over Brussels.